Feature

A Conversation with Addoley Dzegede Daniel Giles

From the fall of 2022 through the summer of 2023, Addoley Dzegede was artist-in-residence at the Piet Zwart Institute Master Fine Art. During this time, Addoley was based at the MFA studio building at Karel Doormanhof 45 where she pursued her Fulbright research project “Exploring textile lineages in Dutch collections through dyeing, batik, and wax print histories.” Below, Course Director Daniel Giles and Addoley Dzegede share some reminiscences about Addoley’s time in the Netherlands and at the Piet. An introduction to Addoley’s book Cut from a Bigger Cloth: Explorations in Batik, Dye, and Wax Print produced toward the end of her residency is also included here.

Addoley Dzegede in the Fabric Station, demonstrating various ways to make batik during the “Color + Conquest” intensive. Photo: Daniel Giles

Addoley Dzegede in the Fabric Station, demonstrating various ways to make batik during the “Color + Conquest” intensive. Photo: Daniel Giles

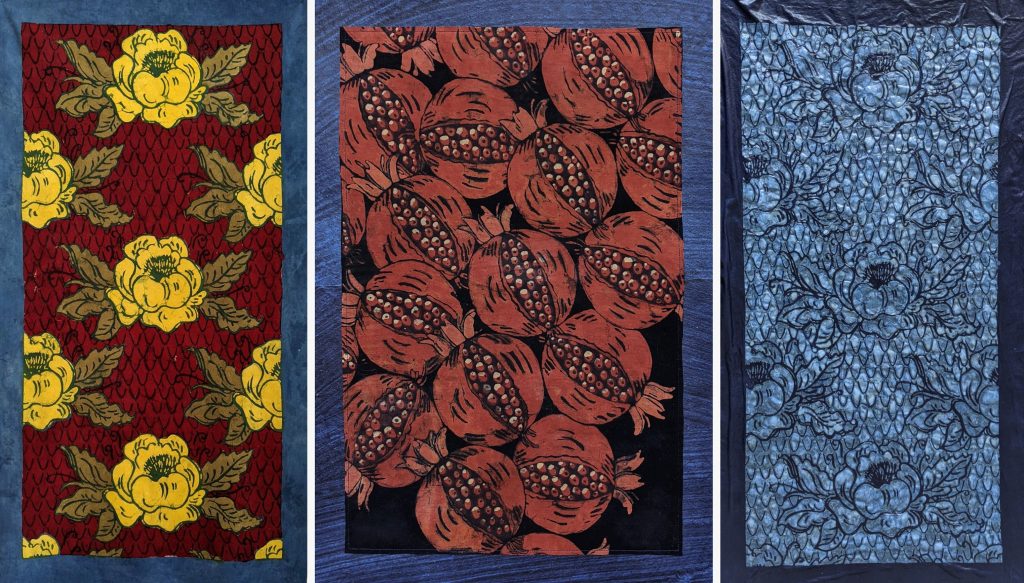

Addoley’s batik samples. Photo: Daniel Giles

Addoley’s batik samples. Photo: Daniel Giles

Daniel Giles: It’s already been almost half a year since you finished your Fulbright fellowship but it still feels like just yesterday that you were here in the building with us. I was thinking of this as a kind of exit interview where we could think back and reflect on the time together. Thanks for making some time to reminisce with me.

Addoley Dzegede: Thanks for the opportunity to reflect. In some ways I also feel like it was just yesterday, and in other ways I feel like it was a lifetime ago that I was standing in a patch of sun drinking tea in the studio while looking at all my seedlings.

DG: You were in residence at the Piet MFA studios for a year, and you packed a lot of activity into your Fulbright research residency period. It encompassed studio experimentation, research, and some teaching. What were some highlights of your time in the Netherlands? How has this time affected your current practice?

AD: Teaching was definitely a highlight. I got to know quite a few of the MFA students before the class began, just by way of being in the same building everyday, but working together and experiencing the process of discovery together each meeting was invigorating.

Outside of the academic setting, another highlight was attending the In Situ Graduate School on Textile and Dyes as Transnational, Global Knowledge through the International Institute for Asian Studies in Leiden, where I met other textile nerds and got to present on Ghanaian batik and my own work. Also memorable moments include visiting countless museums, going to the Jan Van Eyck Academie and Rijksakademie open studios, giving artist talks at a local Rotterdam high school and an art school in Boxtel, and time spent gardening at PZI.

Left: Dye plant seedlings growing in Addoley’s studio at PZI MFA studios. Right: Miriam Del Seppia planting woad in the garden. Photos: Addoley Dzegede

Left: Dye plant seedlings growing in Addoley’s studio at PZI MFA studios. Right: Miriam Del Seppia planting woad in the garden. Photos: Addoley Dzegede

Steaming eco printing bundles in the Fabric Station. Photo: Addoley Dzegede

Steaming eco printing bundles in the Fabric Station. Photo: Addoley Dzegede

Left: The “flower” on an indigo vat. Right: Addoley painting with aluminum acetate mordant on fabric (which was indigo dyed and batiked) to prepare it for further dyeing. Photos: Addoley Dzegede

Left: The “flower” on an indigo vat. Right: Addoley painting with aluminum acetate mordant on fabric (which was indigo dyed and batiked) to prepare it for further dyeing. Photos: Addoley Dzegede

DG: Part of your residency with the MFA included teaching a thematic seminar, Color and Conquest, which intertwined making with research into color’s relationship to imperialism and colonialism. How was it to work through these ideas with the MFA students in the WdKA fabric station?

AD: It was challenging to really get engrossed in discussion when it was clear everyone (including myself!) was itching to get their hands in the dye pots. I made space to talk about the assigned readings, but thought of them more as introductions that could spark longer individual journeys for each student, as well as provide a foundational introduction to the fascinating world of textile histories—from the stink of Tyrian purple squeezed from Murex shellfish to dye the clothing of the wealthy, to failed attempts to take cochineal insects and the nopal cactus they grow on from colonial Mexico to Europe, to the prosperity of the US South built on the labor and knowledge of enslaved African people in the indigo and cotton fields.

What felt like success for me was seeing two students (Miriam Del Seppia and Ifigeneia Ilia-Georgiadou) use work they made in the thematic seminar in their thesis exhibitions. It made it clear to me that someone had walked away somehow changed by taking the seminar.

DG: Your fellowship and residency period ended with the production of a book that shares experiences and insights from your artistic practice and research on fabric prints and natural dye production. It was a big undertaking that you handled in a short period of time. The book is also kind of like a memoir of sorts. Has the project led to any new insights or ideas about your work or life story?

AD: I still can’t believe sometimes that I did all that work in less than four months and right at the end. But that goes to show that a lot of the work that we do as artists isn’t “the work” that people see; it includes all the experiences and knowledge we build over time and through experimentation, reflection, and community. One thing the book did do is make me see that all coalesce; it provided a way to funnel everything into one eclectic object.

If someone asked me to make an exhibition of the work I made while I was in the Netherlands, I would have some hesitation. What I have is a lot of tests, many “failures,” and few “successes” because, it turns out, natural dyeing is challenging! Especially because I was trying to combine it with batik. Honestly, finishing the book was really stressful. For example, I was packing up my stuff to leave the Netherlands the same week I was heading to Maastricht for the book launch (at Limestone Books), in the same week I was picking up a tapestry I made at the Textielmuseum in Tilburg. It was a whirlwind! I worked with my brilliant friend Karoline Świeżyński, who is an incredible designer, and my partner Lyndon helped with a lot of the grunt work (testing dye recipes, cutting swatches, etc) to finish the book. To top it off, we all managed to catch COVID-19, each three weeks after the other.

Left: Mordant painting and printing with natural dyes. Center: Madder (meekrap) and indigo batik. Right: Batik fabric dyed in indigo, before the wax was removed. Photos: Addoley Dzegede

Left: Mordant painting and printing with natural dyes. Center: Madder (meekrap) and indigo batik. Right: Batik fabric dyed in indigo, before the wax was removed. Photos: Addoley Dzegede

DG: I’m curious about your artistic influences outside of the Vlisco textile patterns and African prints that you have researched and responded to in your work. What other artists or designers have helped to shape or feel in dialogue with your work?

AD: I tend to be influenced most by the anonymous artists who made the decorative and perhaps now-strange objects that we see in museums which once had significant meaning and/or daily purpose but no longer seem to. I am influenced by the milieu of everyday life… the stained glass in a chapel, the shape of tile in my childhood home, the strangeness of a bronze aged crotal. I am inspired by family history, by stories and by thoughts that come to me when I give my mind the chance to wander.

DG: We were also lucky to have your collaborator and partner Lyndon Barrois Jr visit the course as a guest tutor last year. You two have collaborated for several years now as LAB:D, can you talk about how working collaboratively relates to your overall practice?

AD: We have thought of working together in many ways: as a chance to reflect (Elleboog, 2019), to overlap our interests (Mercantile, 2022), to create space for fun and imagination (Wayfarer, 2018), to encompass ideas outside of our individual work (The Truth is Rude, 2015). Basically, even though we both work in a wide variety of media and topics already, our collaboration gives us a chance to make outside of the bubbles we have created for ourselves.

DG: You have had several different experiences with living and working abroad, what advice would you give to other artists who want to pursue these kinds of opportunities and uproot their practice to a new context?

AD: The less complicated your life is the easier it is to do this. I would say think about what means the most to you and cut back the rest. I don’t have pets, and I don’t aspire to own a house or car. I don’t have children. I reflected a whole lot over the last two decades and decided those things were not going to be part of my goals for life. For someone else, they might cut out things that I love and choose differently. Being able to uproot a practice will look different for everyone, and the ability to do so changes depending on the particularities of your life, whether it be caring for family members, disability, debt, the economy and support for the arts, or being a citizen of a country without passport privilege.

My advice would be to talk to artists you meet who have done what you want to do and ask how it was possible. I would say, look for and apply for local (less competition) and national grants regularly, make and stick to a budget, see if your job will give you unpaid leave, apply for more funding than you think a project needs, and look for residencies/opportunities that fit your needs (for instance, there are family-friendly ones for people with kids). In the early years of me doing residencies, I was working up to three part-time jobs at a time to save up for when I wasn’t working (and also because those jobs were easier to come back to after being away). I feel like the less comfortable/cushy I make my daily life, the more freedom I have to leave it.

DG: Are there any exciting projects on the horizon that you can share?

AD: I’m going to be teaching a workshop at Haystack Mountain School this summer, which I hear is an amazing creative atmosphere that draws in really enthusiastic students, so I’m looking forward to that. I also recently took an intro stained glass course when I was in residence at Frick Pittsburgh through AMLA|LEWIS, and so I’ve become obsessed and taken on yet another labor intensive medium. I’m excited to see if it lasts or becomes a passing obsession, but regardless, it has made me realize how much stained glass I encounter everyday and learn more about the history and techniques.

I just want to say thanks again to you Danny, and Petra, and all the students for the role you played in one of the best years of my life!

Wild madder grown in the studio (dye comes from the roots). Photo: Daniel Giles

Wild madder grown in the studio (dye comes from the roots). Photo: Daniel Giles

Part of Addoley’s studio set up for dyeing. Photo: Daniel Giles

Part of Addoley’s studio set up for dyeing. Photo: Daniel Giles

Cut from a Bigger Cloth: Explorations in Batik, Dye, and Wax Print – An introduction by Addoley Dzegede

In the summer of 2021, I was living in Tulsa, Oklahoma, for a long artist residency/fellowship. I had started there in August of 2020, and things were slow and unusual because of the pandemic. The monthly open studios that had been required of fellows in previous years no longer applied, and all meetings and events were relegated to Zoom. I never met some of the other fellows in person, and I saw little of the city because I don’t own a car and was avoiding public transport. I was mostly having groceries delivered and living a small life between my apartment and studio. The world seemed like it was, if not coming to an end, different. I thought everything we had valued before would be questioned and that we would somehow emerge better, kinder, versions of ourselves, more appreciative of the little things. While I felt anxiety, and at times fear, I also felt a sense of relief from my normal ambitions and finally had the time for something that had once been an “early twenties” goal: to learn to speak another language. From August 1, 2020, I immersed myself in the Spanish language—and not like the weak attempts I had tried before. I decided there were no books to be studied, no formal classes to be taken. I trusted all of the self-directed language learners who sat in front of a camera and told the world how they had done it: with movies, language partners, curiosity and dedication. And so for the first time in many years, making art took second place in my life. I still worked on a few collaborations and commissions, made five portraits at a snail’s pace, designed and started three larger pieces, and made a new body of work for a show with my partner, Lyndon, about the color blue. But it was different. It was something I fit in around my Spanish conversations, series, podcasts, and short stories.

Perhaps this seems a strange introduction to a book about my creative research year in the Netherlands, but I still find it curious how it came about. I had been learning Spanish for almost a full year and felt really good about my accomplishments, but I wanted to take it to another level and be immersed. I had traveled only as far as Pittsburgh, to visit Lyndon at what was now our home base because of his university job, and I was dreaming of new adventures beyond the four walls of my room and studio. I had traveled virtually all around Latin America, talking to tutors and language partners in Colombia, Spain, Mexico, Venezuela and more; and I was ready to see what it was like to try to talk in a group, to understand what someone was saying when traffic was passing and I couldn’t see their mouth, to spontaneously respond to problems and circumstances that arise in the real world. And for some reason, this led me to the idea of applying for a Fulbright to Mexico.

I had attempted to start the Fulbright process before in 2016, but I had given up when I was told in late August that most applicants had started working on their materials months before. So half a decade later, in July of 2021, I had a meeting over the phone with Erin Treacy, the Fulbright coordinator at Maryland Institute College of Art, my undergraduate alma mater. I expressed my desire to apply for Mexico, but admitted that the Netherlands was a better fit in terms of the content of my work and connections. She asked:

What about your project makes it uniquely suited for the country you are interested in applying to for the Fulbright Fellowship?

And I answered:

About five years ago, I started incorporating batik into my processes and making works that refer to the material histories, specifically wax prints and trade beads, that continue to tie the Netherlands culturally to Ghana (where I am also a citizen in addition to the US).

To summarize my interests, I am fascinated by ideas of “authenticity,” as it suggests ideas of “purity” when it comes to cultural production. In truth, many traditions arrive from the results of cross-cultural interactions. A prime example of this is the case of handmade Indonesian batik giving rise to industrially produced wax prints in the Netherlands, which are now globally associated with parts of Africa. The most prominent wax print fabrics are still designed and printed in the Netherlands by Vlisco.

I am also interested in chintz fabrics which are used in traditional Dutch clothing but originated in India. I create my own textiles that have specific references to locations and histories that can be read by those who know the signs and symbols. The Netherlands is a place where cross-cultural influences are made evident in many decorative items and textiles. I gather a lot of inspiration for projects from museum visits, and the Netherlands has 438 museums packed into a relatively small land mass. A lot of my work has dealt with trade histories—from the movement of indigo and trade beads, to textile processes and motifs. As a country with a long and complicated trade history, it makes the most sense as a place to further my research and work.

And so began my journey to find affiliations in the Netherlands. I had met batik researcher Sabine Bolk many years before, but she worked independently and was not an employee at an institution that would sponsor me. Susie Brandt, fiber artist and my favorite professor at MICA, put me in touch with Annet Couwenberg, who also teaches at MICA and is Dutch and has more knowledge of Dutch institutions. Annet put me in touch with Dr. Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, director of the Textile Research Centre in Leiden, and I had an affiliation, though not one that could sponsor me. I met virtually with Danny Giles, an artist I had met at the Black Artist Retreat in Chicago in 2016, and now course director at the Piet Zwart Institute, and told him about my proposal. He was interested and wrote:

One idea is to host a workshop on natural dyes to explore the process and colonial histories tied to materials like indigo. We have spent the last year revitalizing our garden and I’m interested to make connections between plants, history, and artistic research and practice. This sounds like it could be along the lines of what you’re thinking, and I’d be very happy to think with you about how your work intersects these ideas.

And so the seed was planted for what became my Fulbright project. What I had once seen as two separate aspects of my work—experiments in natural dyeing with plants growing where I worked, and wax print-inspired works—came together in the plan. My friend and across-the-hall-neighbor in Tulsa, Jen Choi, is a fantastic writer and editor, and she helped me take my museum exploration idea and meld it with Danny’s garden and workshop idea into a concise seed-to-color concept.

And so I write this introduction to you while in Rotterdam. The project has not been linear, simple or even “successful” in the ways I imagined. It has been more of a meandering journey, one with anxieties, failures and doubts as well as unexpected encounters and moments of joy. This book is not meant to teach you how to dye (though there are recipes and tips), how to garden, or go in depth into the history of batik or wax print. Rather it is meant to spark your curiosity, make you want to learn or do more, to share what I have done in the past and learned during this time, and to introduce you to who I have met during my time here. I have at times not known where to focus my energies and so, like seeds, I have scattered them: meeting new people, talking about color, reading about color, experimenting in the studio and classroom, teaching others, learning from others, watching things grow, trying to somehow be a better version of myself, and to be more appreciative of the little things.

8 May 2023, Rotterdam

Addoley Dzegede is a Ghanaian-American artist who grew up in South Florida and has a home base in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She was recently a 2022–2023 Fulbright awardee in Craft to the Netherlands and based in Rotterdam for the duration of the award as the Artist-Researcher-in-Residence at Piet Zwart Institute. She was recently the inaugural Artist-in-Residence for a collaboration between ALMA|LEWIS and Frick Pittsburgh. Her work has been exhibited throughout the US, Europe, and Africa, and she has been an Artist-in-Residence at AiR Green in Noresund, Norway; Loghaven in Knoxville, Tennessee; the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida; Osei Duro in Accra, Ghana; Thread: a project of the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in Senegal; Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris; The University of Kansas; and several other institutions, as well as a post-graduate apprentice at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia. She received a BFA from Maryland Institute College of Art, and fellowships include the Chancellor’s Graduate Fellowship at Washington University in St. Louis, where she completed an MFA degree in Visual Art, and the Tulsa Artist Fellowship. Group exhibitions and screenings include The Real Show at CAC Brétigny, France, A Structure Envisioned for Changing Circumstances; Season 3 of the “Ask Addoley + Anna” podcast with Anna Ihle commissioned by The National Museum of Norway for I Call It Art; SOM at Penn State Abington in Pennsylvania; Season 2 of the “Ask Addoley + Anna” podcast commissioned by Coast Contemporary for Organized Freedom in Norway; This Country at Wesleyan University in Middletown, CT; Overview is a Place at SPRING/BREAK Art Show: Stranger Comes to Town in New York; Another Country at 50/50 in Kansas City; the Counterpublic Triennial, organized by The Luminary, St. Louis, MO; Color Key at the Contemporary Art Museum, St. Louis; and Surface Forms at The Fabric Workshop & Museum in Philadelphia. Dzegede was a 2018 recipient of the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Grants. Other awards include a 2018 Great Rivers Biennial award; a MICA alumni award; a St. Louis Regional Arts Commission Artist Support Grant; and a Creative Stimulus Award from Critical Mass for the Visual Arts. Her solo exhibition, Ballast, was on view in the summer of 2018 at the Contemporary Art Museum in St. Louis as part of the Great Rivers Biennial, and millefiori at KSMoCA in 2020. She is half of the collaborative duo, LAB:D, with Lyndon Barrois Jr, most recently exhibiting works together in Mercantile at Sharp Projects in Copenhagen, Denmark and at Chart Art Fair.